| |

Colon Panel

Ref.-No.: 40050000

COLON PANEL FOR DETECTION OF INFLAMMATORY FACTORS IN THE BOWEL

Colon Panel represent a new generation of multi-parameter „One Step“ device, it is able to detect simultaneously different a qualitatively parameter useful for the diagnosis of bowel inflammation as Hemoglobin, Calprotectin, Escherichia Coli, Lactoferrin, and Transferrin in human bowel. This device is for professional use only and for IVD (in vitro diagnostic medical device).

INTRODUZIONE E PREMESSA GENERALE

The colon is the last part of the digestive system in most vertebrates; it extracts water and salt from solid wastes before they are eliminated from the body, and is the site in which flora-aided (largely bacterial) fermentation of unabsorbed material occurs. Unlike the small intestine, the colon does not play a major role in absorption of foods and nutrients. However, the colon does absorb water, sodium and some fat soluble vitamins. In mammals, the colon consists of four sections: the ascending colon, the transverse colon, the descending colon, and the sigmoid colon (the proximal colon usually refers to the ascending colon and transverse colon). The cecum, colon, colon rectum and anal canal make up the large intestine The large intestine is mainly responsible for storing waste, reclaiming water, maintaining the water balance, absorbing some vitamins, such as vitamin K, and providing a location for flora-aided fermentation. By the time the chime has reached this tube, most nutrients and 90% of the water have been absorbed by the body. At this point some electrolytes like sodium, magnesium, and chloride are left as well as indigestible parts of ingested food (e.g., a large part of ingested amylose, starch which has been shielded from digestion heretofore, and dietary fiber, which is largely indigestible carbohydrate in either soluble or insoluble form).

As the chyme moves through the large intestine, most of the remaining water is removed, while the chyme is mixed with mucus and bacteria(known as gut flora), and becomes feces. The ascending colon receives fecal material as a liquid. The muscles of the colon then move the watery waste material forward and slowly absorb all the excess water. The stools gradually solidify as they move along into the descending colon. The bacteria break down some of the fiber for their own nourishment and create acetate, propionate, and butyrate as waste products, which in turn are used by the cell lining of the colon for nourishment. No protein is made available. In humans, perhaps 10% of the undigested carbohydrate thus becomes available; in other animals, including other apes and primates, who have proportionally larger colons, more is made available, thus permitting a higher portion of plant material in the diet. This is an example of a symbiotic relationship and provides about one hundred calories a day to the body. The large intestine produces no digestive enzymes — chemical digestion is completed in the small intestine before the chyme reaches the large intestine. The pH in the colon varies between 5.5 and 7 (slightly acidic to neutral).

The colon is prone to different inflammatory disease that compromise its functioning. Colitis, for example, is the general term to indicate the condition in which the colon is sore. This condition can configure a large number of pathology, which could be different in etiology. Though, they are all united by the inflamed mucosa and by a very similar symptomatology. The most common diseases which belong to this kind of infection are:

Infectious colitis: the colon is susceptible to infection. Sometimes this is caused by dangerous bacteria gaining access to the colon via contaminated food, and other times it is caused by overgrowth of the bacteria (which can be caused by antibiotic use).

Ischemic colitis: is a medical condition in which inflammation and injury of the large intestine result from inadequate blood supply. Although uncommon in the general population, ischemic colitis occurs with greater frequency in the elderly, and is the most common form of bowel ischemia.

Ulcerative colitis: is a form of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Ulcerative colitis is a form of colitis, a disease of the colon (large intestine), that includes characteristic ulcers, or open sores. The main symptom of active disease is usually constant diarrhea mixed with blood, of gradual onset. IBD is often confused with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), a troublesome, but much less serious, condition.

Crohn’s disease: also known as regional enteritis, is a type of inflammatory bowel disease that may affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract from mouth to anus, causing a wide variety of symptoms. It primarily causes abdominal pain, diarrhea (which may be bloody if inflammation is at its worst), vomiting (can be continuous), or weight loss

Irritable bowel syndrome: is a symptom-based diagnosis characterized by chronic abdominal pain, discomfort, bloating, and alteration of bowel habits. As a functional bowel disorder, IBS has no known organic cause. Diarrhea or constipation may predominate, or they may alternate

General symptom of the inflamed colon

Pain in the lower abdomen that may be attenuated with defecation. Diarrhea. More than 3 bowel movements per day with altered stool consistency (unformed and liquid). Presence of mucus in the stool. Presence of blood in the stool. Constipation. Less than three bowel movements a week with hard stool consistency Tenesmus. Spasm of the anus, accompanied by uncontrollable feeling of having to defecate. Borborygmi, bloating and flatulence. Pain in the anus and the surrounding area. Bloated or distended. Accompanied by swelling of the stomach: indigestion, stomach pain, heaviness, early satiety, nausea. Bitter mouth, bad breath, burning in the mouth. In this purely symptoms of bowel may become associated urinary and gynecological problems such as the following: Continue urinary urgency of urination. Pain in the pubic region. Constant need to urinate during sleep. Problematic because painful intercourse. Intense menstrual pain. And again the following general disorders: muscle aches and / or head. Dizziness. Generalized fatigue. Dermatitis nervous disposition. Anxiety and depression. Obviously symptoms previously described are all possible of the inflamed colon and normally are present only some of them.

Colon Panel

Colon Panel is a diagnostic device „One Step“, it has an immediate visual result and it is an IVD (in vitro diagnostic medical device). This device has been created in order to provide to the user important qualitative clinical parameters that are essentials in evaluating the inflammatory state of the colon with a simple collection of stools. The device has small dimensions, it is easy to use and it does not require dedicated equipment. In the windows of the device are shown in a few minutes various quality levels of the inflammatory state of the colon.

Principle of the system

The Colon Panel device is composed of several membranes sensitized by specific target which use the immunochromatographic technique well known as Lateral Flow Immuno Assay (LFIA). Colon panel is simple, fast, accurate and reproducible, it gives a complete picture of the bowel inflammation condition to doctors. This method combines the specificity and safety of the serological test with a user-friendly format. Colon panel allows full-field use with a simple collection of stool sample.

Each test present on the membranes of the Colon Panel device uses a combination of monoclonal antibodies conjugated with a specific dye gold-colloidal which highlights the reaction. After the collection of the sample through the apposite test tube that contains the solution in dilution, the stools sample is dissolved and dispensed in the device tank. The diluted sample will fill the tank by exerting pressure on the test tube walls. Then it will go through the membrane thanks to capillarity.

The dye gold-colloidal binds with the specific analyzed antigen, eventually present in the sample, making a complex antigen – antibody. This complex binds with the antibody present in the membrane. If the answer is positive, there will be a pink strip in the Test area (T). If the antigen is not present, there won’t be any strip in the Test area (T). The sample keeps migrating thanks to capillarity along the absorbing device. It goes through the Test area until the control areas (C). Here the free colloidal binds with the reagent, making a coloured strip, in order to prove that the reagents are correctly working.

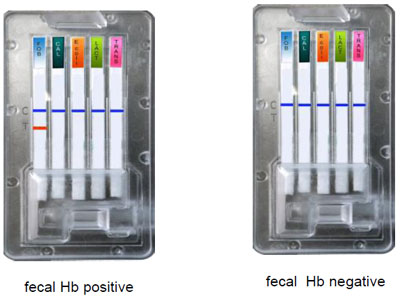

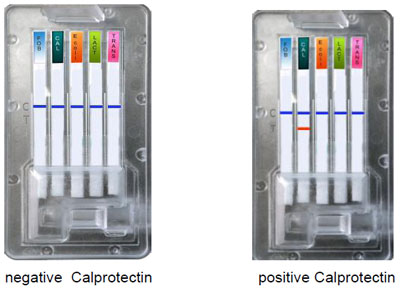

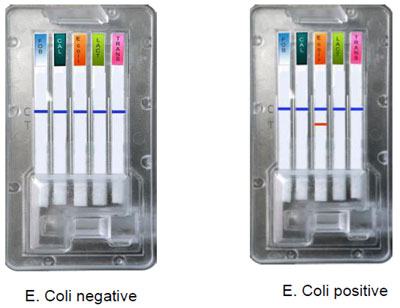

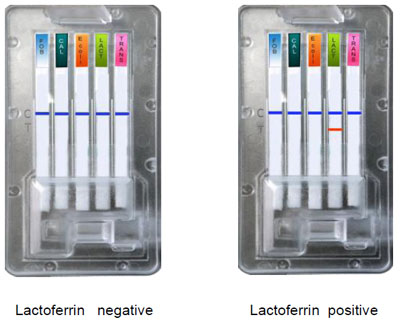

Interpretation of results

The intensity of the coloured band in the test area (T) depends on the sample concentration of antigen. However, neither the quantitative value nor the increase (in percentage) of the parameter rate can be determined by this qualitative test.

Warning

Colon Panel provides only qualitative indications of the pathological state taken in exam. With this system neither the quantitative values nor the increase (in percentage) of the concentration can be determined ; if the system gives positive results, it is better to elaborate specific research with other diagnostic techniques and further close examination. This device is for laboratory professional and medical study only.

Selected test present in the Colon Panel

- Determination of fecal occult blood

- Determination of fecal Calprotectin

- Determination of Echerichia coli

- Determination of fecal Lactoferrin

- Determination of fecal Transferrin

1. Determination of fecal occult blood

A fecal occult blood test checks for hidden blood in the stool and it represents an important screening test to detect colorectal cancer. It is important to underline that, as all the methodical screening, the detection of occult blood in stools DOES NOT have a diagnostic meaning, it simply identifies people who risk this pathology and helps detective the possible presence of intestinal polyp. It is better to advise further accurate diagnostic examination (like colonoscopy) when microscopic blood is detected. There are other possible condition that make occult blood detection possible: gastrointestinal bleeding, ulcerative colitis, Crohn’s disease, diverticular disease, anal fissures, haemorrhoids, abnormalities of the blood vessels in the large intestine, intestinal infections that cause inflammation of the varicose veins of the esophagus, contamination of the sample with period or urinary blood. A special diet is not recommended because test results are not affected by it. The detection of occult blood in the stools remains a precious research to carry out important diagnosis. It leads to better prognosis. Occult blood test is suggested also even if this symptoms are not present. Often, colorectal cancer does not give any particular sign for years. Thus, even if a recent exam has had a negative answer, it is always advisable to consult a doctor when having this kind of symptoms: persistent modification of intestinal habits; visual presence of fecal blood; rectal obstructed feeling after evacuation.

Sensitivity and specificity

A sample that contains human haemoglobin with concentration equal or superior to 50 ng/ml produces a positive results to the stool occult blood. In some cases the sample containing human haemoglobin with concentration inferior to 50 ng/ ml can also be tested as positive. Different dilutions of haemoglobin have been tested directly in the extraction tampon or they have been diluted in a negative stool sample according to the kit instructions. The human haemoglobin survey in the occult blood test has conveyed a sensibility > 99% compared to the guaiac method. The occult blood test is specific for human haemoglobin and it does not show cross reactivity with other animals haemoglobin. The human haemoglobin survey has conveyed a specificity >99% compared to the guaiac method. The use of monoclonal murine antibody provides an high level of specificity in order to survey human haemoglobin.

Test interpretations

A coloured band must appear in the test control line which certifies the product performance. High concentration of antigen O157:H7 can give a slight visualization of the strip. This could question the test precision. The test is negative if only one coloured strip appears in the test control section. If in the Test zone a coloration appears, even if feeble, test must be considered positive. The strip presence in the test zone is index of the test positivity. The test is invalid if no colouring appears or if only appears in the coloured strip in the Test zone.

2. Determination of fecal Calprotectin

Calprotectin is a neutrophil cytosolic protein with antimicrobial properties. It is largely present in cytosol, less present in monocyte and macrophages. Calprotectin, in vitro, seems to possess bacteriostatic and fungistatic activities. Calprotectin is mostly present in neutrophil, its determination in stools is utilized as a marker of neutrophil infiltration in the intestinal lumen. It is also used as an indirect marker of intestinal inflammation. Studies supporting this application show that increased levels of fecal calprotectin can be noticed mainly in IBD Inflammatory Bowel Disease (Ulcer colitis, Crohn’s disease), and in some gastrointestinal neoplasias. Increased levels can also be noticed in all the pathologies that imply an inflamed process, chronic or acute, which is on the gastrointestinal system. They include peptic pathologies , diverticulitis, infectious enterocolitis and some medicine treatment. Detect fecal calprotectin cannot replace the modern invasive practices used to diagnose Crohn’s disease. In fact, endoscopic techniques of imaging and histology remains the „gold standard“ for definitive diagnosis of Crohn’s disease. The determination of fecal calprotectin is a useful marker of the diseases state. It is simple, non invasive and inexpensive.

In order to utilize the test this indication must be taken: monitoring the intestinal inflammatory activity, it is a pathology marker indicator. It is useful in the therapeutic follow – up, it is also useful in order to exclude any IBD in subjects with chronic diarrhea or unknown chronic abdominal pain. It is an excellent neoplastic marker and used for most of the gastrointestinal inflammatory diseases. It is also excellent in detecting acute inflammation, it is an indicator of the gastrointestinal inflammatory damage. The test is also useful in monitoring Crohn’s disease, ulcer colitis and in monitoring patient after having removed intestinal polyps. It is more than useful in the differentiation between the acute phase of Crohn’s, ulcer colitis and irritable colon syndrome.

Sensibility and Specificity, interference and cross – reactivity

Sample that contain levels of calprotectin with stool concentration equal or superior to 50μg/g produce positive results. Different dilutions of calprotectin have been tested directly in the extraction buffer or in a negative stool sample in order to determine the test detection limits. Calprotectin test has shown a sensibility level >94% compared to other tests now in business. Similarly the detection of human calprotectin with this device has shown a specificity of 93%. This test is specific for human calprotectin and it does not have any cross – reactivity with other animals calprotectin.

Expected values.

High values of calprotectin in stools are associated to increasing risk of relapse in patients with an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Some studies have determined a cut – off equal or higher to 50-70 μg/g of calprotectin fecal which has allowed to detect adult patients with gastrointestinal inflammatory problems.

Interpretation of results.

See the section of „Interpretation of results“ in occult blood test.

1. Escherichia Coli

Foodborne diseases are illness caused by specific foods or food groups contaminated by chemicals or biological agents. This area gives possibility to detect alimentary infections, toxinfections and food poisoning. Foodborne diseases are mainly shown with an acute gastroenteritis symptomatology. The most common cause of gastroenteritis is the infection of the digestive system. It typically manifests itself with the sudden appearance of diarrhea, it may be accompanied by fever, abdominal pain, which can ease with defecation. Often both vomiting (especially in food poisoning case) and general signs of infections (for example muscle pain, headache, nausea and lacking appetite) are present. Stools can be completely liquid, soft or half formed, they are often mixed to mucus. In particular circumstances stools can be mixed to blood, in that case it must be considered dysentery. The most known food infections are the ones causes by bacteria: Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, Yesinia enterocolitica, Escherichia coli; and from virus: Rotavirus, Adenovirus and Norwalk virus.

Escherichia coli is the most known species of the Escherichia genre. Although more than 50.000 serotypes have been typify, the larger part is constituted by commensally microorganism (non – pathogenic). Only a restricted number of strain is capable of inducing the disease. The different serotype are characterized by different antigens combination O, H, K, F (O:somatic; K: capsular; H: flagellate; F: fimbriae).

Escherichia coli is one of the principal bacteria species that live in the inferior intestinal part of hot – blooded animal (birds and mammals included). It contributes to the correct digestion of food. Its presence in the water bearing stratum commonly indicates contamination by stools. From the clinical point of view: there are 5 important groups of Escherichia coli: enteropathogens, enterotoxigenic, enteroinvasive, enteroadherent and enterohaemorrhagic. The E. coli O157: H7 was identified for the first time as a pathogen in USA and in Canada in 1982, after a haemorrhagic diarrhea associated to the fast food consumption of hamburger. Its peculiar characteristic is the high resistance to low temperature. It can resist up to nine month with -80°C.

Another important characteristic, that can affect the capability of colonizing the human intestine, is the resistance to the stomach acidity. Fortunately, this pathogen is very sensitive to high temperature (44-45°C); thus, it is fundamental to cook rightly in order to ensure the security of food. Main virulence factors of Escherichia coli O157:H/ are two toxins produced ( Stx1 and Stx2) which cause cellular damage to the intestinal mucosa (enterocytes). When starting their circulation they can also damage kidney, compromising its function.

Adult and child therapy is based on rehydration and on the correction of electrolytic alterations, as well as the acid – based equilibrium and the correction of the eventual bleeding. Antibiotic therapy is not recommended because it could increase the toxin release. It could also worsen the patients general conditions. Most critical patients need an intensive treatment based on dialysis , blood transfusion which could lead to kidney transplantation. The present test in the Colon Panel belongs to the qualitative genre, it determines whether E. coli O157:H7 is presence or not.

Interpretation of results.

See the section of „Interpretation of results“ in occult blood test.

4. Determination of fecal Lactoferrin

Lactoferrin and leukocytes are present in stools mainly in patients affected by Salmonella, Shigella, Campylobacter, Yiersina, Vibrio non cholerae, Aeromonas and Clostridium difficile. Even if there is presence of blood in the intestinal amoebiasis there is a small quantity of leukocytes. The detection of leukocytes in fresh stools is an economical examination, but it must be executed by an expert microscopist. Lactoferrin measurement in stools with the immunochromatographic method is simpler, more reproducible, and immediate. The fecal lactoferrin will appear significantly increased in the active ulcer colitis and in the Crohn’s disease. A direct comparison between lysozyme, lactoferrin, myeloperoxidase and human polymorphonuclear leukocyte shows how lactoferrin is the best inflammatory marker which derives from neutrophil.

Several clinical indication result from the test. One is its use as a control of the intestinal inflammation, of the bacterial infections, of the parasitic infections. Also its use as a monitor of Crohn’s disease and ulcers colitis in close relation with calprotectin.

Performance

In infective intestinal diseases has been observed that the largest part of neutrophil circulating tend to migrate in the infected tissue where they release different components. Lactoferrin has been associated to some specific secondary components which during the phagocytosis are released simultaneously to other lysosomal proteins. Concerning this, lactoferrin has been identified as a marker of the leukocytary activity in the intestinal infections. The corresponding increasing of the leukocytes fecal presence has given the indication of an inflammatory answer to the bacterial infections. On the contrary the bigger part of viral infections seem to be an invasive inflammatory process with a low migration of neutrophil.

Sensibility and specificity, interference and cross – reactivity

A sample of stools containing lactoferrin with a concentration equal or higher to 10ug hLf/g gives a positive result. As a check, different lactoferrin dilution have been tested directly in the extraction tampon. Or they have been added to a negative fecal sample and have been tested to evaluate the limit reliability of the test. The determination of lactoferrin in the colon panel has detected a sensibility >99% respect to other test on business. The test is specific to human lactoferrin; no cross – reactivity has been detected with other animal lactoferrin.

Interpretation of results.

See the section of „Interpretation of results“ in occult blood test.

Determination of fecal Transferrin

Transferrin is a blood plasma protein. The main function of this protein is to deliver iron to the circulatory system. Trasferrin is synthesized by liver and monocytes – macrophages system. Transferrin is capable of permanently but reversibly bind gastrointestinal absorbed iron and iron derived from red cells (erythrocytes). The iron is thus delivered to the bone marrow and to the liver. Plasma transferring is an 80 kDa glycoprotein, formed by a polypeptide chain containing 679 amino acids. Transferrin has a molecular weight around 80 KD and 8 days half life. Iron transferring is less then 0,1% of the total body iron. This percentage, though, represents a more dynamic fraction which is characterized by high turnover speed (25 mg/24 h). Transferrin protein has a metal – binding property, and its determination it is less expensive than the direct one.

An interesting survey on proteomics has identified transferring to be a potential biomarker for colorectal cancer. Fecal samples from 110 patients including 40 colorectal cancer, 36 premalignant subjects (including 16 with high-risk adenomas and 20 with ulcerative colitis), and 34 low-risk subjects were collected before colonoscopy examination. Compared with occulted blood test, Transferrin had a significantly higher positive rate in patients with colorectal cancer and premalignant lesions (76% for Transferrin versus 61% for occult blood test). The difference of positivity was mainly observed in patients with premalignant lesions, whereas the positive rates in cancer group and in low-risk group were similar. Combining Transferrin test with occult blood test together (either/or) had 90% positive rate in cancer patients, 78% in premalignant patients, and 29% in low-risk subjects. Transferrin dipstick test seems to be a highly sensitive test for detecting not only cancer, but also premalignant lesions, and provides an additional tool for colorectal cancer screening. Furthermore the determination of possible cancer pathologies of the upper gastrointestinal tract, is actually distorted by the hemoglobin dipstick in stools. Human hemoglobin, in fact, derives from the upper digestive system tract, it is then digested by the intestinal tract with consequent loss of antigenic action. Fecal Transferrin, which results more stable in stools then in hemoglobin, gives a chance of being a method for upper digestive system tract disease diagnosis.

Indications

The application of the system is particularly indicated for common upper gastrointestinal bleeding case such as:

|

Upper tract

|

Lower tract

|

|

duodenal Ulcer

gastric or duodenal erosions

varicose vein

gastric ulcer

erosive esophagitis

angioma

arteriovenous malformation

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor

|

anal rhagades

Angiodysplasia (vascular ectasia)

colitis (ischemic and vascular)

colon cancer

colon polyps

diverticulum colon disease

intestinal bowel disease

proctitis/ colitis

Chron’s disease

internal hemorrhoids

|

Sensibility and specificity

The limit detection of fecal transferrin is 0.4 mg/g. The system of fecal transferin has a specificity >99% and a sensibility >99%, comparing the elements with guaiac occult blood test. A transferrin containing sample with concentration equal or higher then 0,4 mg/g in stools produces positive results when the Colon Panel is used. Different transferrin dilutions have been carried out in the extraction tampon. Or they have been diluted in a negative stool sample to determine the revelation limit test. Revelation limit values have been noticed: 4ng/ml of human transferrin.

Sensibility:

transferrin test has expressed a sensibility >99% compared to classical guaiac test. The test is specific for human transferrin and it has not underlined any cross – reactivity with other animal transferrin.

Specificity:

transferrin test has expressed a specificity >99% compared to classical guaiac test. The use of mouse monoclonal antibody in the test guarantees a high – grade specificity in revealing human transferrin

Interference and cross – reactivity

An evaluation to determine any possible interference and cross – reactivity has been lead. No cross reactivity has been detected neither in common gastrointestinal pathogens, nor in other organism and material occasionally present in the stools. No interference has been verified with food or supplements (as iron).

Limit procedure

Fecal transferrin determination test gives relative indication on transferrin presence in the stools sample (quantitative research). Neither the quantitative value, nor the increasing percentage of transferrin concentration can be determined with this test.

Interpretation of results.

See the section of „Interpretation of results“ in occult blood test.

Stool Specimen Collection.

Please follow carefully the different procedure steps in order to achieve the system correct use and the best performance.

- Stool collection must be carried out by prevailing a sufficient quantity of stool ( 1 – 2 g or ml for each liquid sample)

- Stool specimen must be collected in clean and dry container (no preservative or transportation officials)

- Specimen can be stored in the fridge (2-4ºC/36-40ºF) for 1 up to 2 days before being tested. For longer storage period, specimens must be frozen ( -20°C/4ºF). In this case, the specimen will be completely defrost and tested after reaching an ambient temperature.

Protocollo d’uso

Use the plastic tube containing the storage buffer for each sample that found in the package.

The first operational phase consists in gathering the stools specimen. This is useful to qualitative determine the 5 test present in the Colon Panel. This is an extremely easy and smooth phase. The sampling stool device, contains an amount of dilution solution necessary for the test procedure. When the specimen collection has finished, the sample goes to the diagnostic device after dipping and rotating the stick in the closing cap in 4 – 5 different stool points.

The increasing of both the control band and of the specimen will give to the user in only 5 minutes the intestinal inflammatory state detected in the patient. The sampling stool device allows to gather the amount of stool required for the execution of the test in the Colon Panel directly from the primary container without weighting the specimen.

The sampling device is constituted by a test tube containing 2,0 ml of extraction solution and by a little shaped stick with four radial grooves for the specimen collection. The intermediate extremity is provided with a filter to keep specimen excessive quantity or rough impurity from the sample. The filter can be removed with an horizontal torsion.

Materials provided

Each kit contains 10 Colon Panel cards supplied with the respective sampling containing the extraction solution. The Colon Panel card and the sampling are disposable.

Storage and Stability

Storage card and sampling at 2 – 8 ° C.

Specimen collection and preparation for normal stiffness stools:

- Take the sample to be tested in a sterile container.

- Take the collection device tube rotating the cap anticlockwise

- Dip the stick in 4 – 5 different point of the stool.

- Rotate several times the stick in the sample so that all the stool grooves fill themselves with fecal material.

- Before inserting the stick in the device, remove the rough material rotating the stick in the internal wall of the primary stool container

- Completely insert the stick, with fecal material, in the test tube with dilution liquid and rotate the cap clockwise until its complete closing.

Specimen collection and preparation for liquid stools:

This procedure requires the sampling of 60 μl of liquid stools. It is thus necessary to have a laboratory pipette. Proceed as follows:

- Take the device stick rotating the cap anticlockwise.

- Storage the liquid stools in the collection device.

- Re insert completely the stick in the tube test (which won’t contain stool) and rotate the cap clockwise until its complete closing.

Specimen collection and preparation for hard stools:

- Collect a stool specimen in a sterile container

- Transfer 50-100 μl saline physiological solution in the stool container.

- Container and physiological solution must remain at ambient temperature no less than 60 minutes.

- Proceed from point 2 of „Specimen collection and preparation for normal stiffness stools“.

Specimen collection and preparation without device:

If the centre does not have temporarily the specimen stools devise, collect the sample in a sterile container and maintain it for no more the 2 days at 2 – 4 °C. If the storage period at 2 – 4 ° C passes 2 days, the sample must be frozen at – 20°C. When the device is available, the sampling will be possible according to the instructions described above. If the sample has been frozen let it reach an ambient temperature before proceeding with the sampling. Proceed from point 2 of „Specimen collection and preparation for normal stiffness stools“.

Storage of the device after the collection of the stool specimen:

The collection device containing the stools must be storage in the fridge (2 – 4°C) and must be send to laboratory for testing within 48 hours after the sampling.

Deliver the device containing the sample to the medical laboratory:

if transferring time from the collection centre to the medical laboratory does not exceed 60 minutes, no particular attention is needed. If delivering time takes up to 60 minutes is necessary that the specimen is put in a thermal container with the presence of cooling elements to ensure appropriate conservation.

Procedure use of Colon Panel:

- Take a colon panel packaging, verify the integrity of the package.

- Verify the expiration date of the product, do not use the test longer then the date.

- Carefully read the instructions and cautions and follow them scrupulously before taking the test and open the package.

- Do not use different elements of the ones given in the kit

- Before starting the test bring all the reagent in the kit to an ambient temperature (15-30°C/59-86ºF) before its use (the card, the sampling card, the specimen and / or the controls).

- Do not smoke and do not eat in the area where the test takes place

- If required fill up the patient’s module, being scrupulous in signal the expiration date and the kit lot number used.

Second step

|

When you are ready to perform the test take the sample to be tested (for best results you should use the stool collected previously in a clean, dry container) it is recommended to perform the test within 6 hours of sample collection. The sample can be stored for 3 days at 2-4 ° C.

- Take the collection tube with the extraction /dilution buffer; unscrew the cap with the extractor in the stool sample and dip the stick with a clockwise rotation at least in three different points of the stool.

- Do not dig the stool sample.

- Screw the cap on the collection tube. Now shake the tube vigorously to mix the sample with the extraction buffer.

- Open the package containing the Colon Panel device.

- Place it overturned on the table, remove the protective cap from the connection site.

- Insert the tube containing the diluted sample

- Unscrew the cap / extractor until the complete transfer of the sample into the tank of the device Colon Panel.

- Put some pressure on the side of the sample with your fingers until the diluted specimen comes out.

- Tight the cap to the tube extractor and block the flow by closing the safety cap placed on the side of the device.

- Place the device in an upright position.

|

Look at the release of colloidal gold complex on the membrane. This should be observable as a colored line that moves toward the front of the membrane and should be required from 20 to 30 seconds, depending on the sample, so that it appears. The results of the tests are shown after 5 minutes.

Read the results after 10 minutes could be wrong even if the final outcome remains permanently imprinted for a very long time. Do not perform the test in a room with strong air flow.

REAGENTS AND MATERIALS

Each kit contains:

- 10 card Colon Panel

- 10 extraction tubes containing tampon + labels patient

- 1 Instructions for Use.

Materials not supplied:

- disposable gloves

- stopwatch

- plastic pipettes

Precautions

- This Product is for professional in vitro diagnostic use only.

- Do not use the product after expiration date.

- Colon panel must remain sealed in his original package until its use

- Do not use Colon Panel if the package is damaged

- Follow the laboratory rule, wear protective glasses, use disposable gloves, do not eat, drink or smoke during test execution.

- All the sample must be considered potentially contagious and must be handle as contagious.

- Discard the disposal gloves, the tampons and the tube tester in a proper biohazard container after testing properly.

- After the packaging open test must be done within two hours.

Storage and stability

store the Colon Panel at room temperature or in a cool, dry place, the product has good stability (2-30 º C/36-86 º F).

The product is guaranteed stable until the expiration date printed on the package.

The product should remain sealed in its original packaging until ready to use. do not freeze

Note

Colon Panel exclusively gives temporary results.

It is advisable to confirm through the application of other invasive diagnostic techniques (endoscopy, colonoscopy).

Further clinical considerations together with professional evaluation must be taken into consideration, mostly when test gives positive results. Colon Panel is conceived for professional use only and must not be entrusted nor sold to specialists.

Colon Panel contemporaneously reveal the presence of different gastrointestinal pathologies. Fecal sample screening techniques for this kind of examination can be taken with simple immunochemical methods or with more complex analytical methods. Immunochemical techniques are now well known because of its brevity and high sensibility.

Colon Panel test are based on antibody – antigen reaction to detect various antigens and / o metabolites present in stools.

Qualitätssicherung und Vorkommnisse

Sollten Sie den Eindruck eines Qualitätsmangels haben oder unklare oder ihrerseits falsch-positive oder falsch-negative Ergebnisse erhalten, bitten wir Sie, die betreffende Patientenprobe zurückzustellen und für einen Abruf für uns bereitzuhalten.

Bitte informieren Sie uns umgehend. Sie helfen uns dadurch die Sicherheit der Produkte und damit die Qualität zu gewährleisten.

BIBLIOGRAFY

- Ransohoff DF and Lang CA. Screening for colorectal cancer with the Fecal Occult Blood Test: a background paper. Ann Intern Med. 1997; 126: 811-822.

- Towler BP, Irwig L, Glasziou P, Weller D, Kewenter J. Screening for colorectal cancer using the faecal occult blood test, Hemoccult. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2): CD001216.

- Ransohoff DF and Lang CA. Suggested technique for Faecal Occult Blood testing and interpretation in colorectal cancer screening. Ann Intern Med. 1997; 126: 808-810.

- Chien-Hua Chiang et al., „A Comparative Study of Three Fecal Occult Blood Test in Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding“. Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. May 2006, 22; 223-228.

- Virtanen et al., „Higher concentrations of serum transferrin receptor in children than in adults“, Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999; 69: 256-60.

- Angriman I. et al. Enzymes in feces: Useful markers of chronic inflammatory bowel disease. Clinica Chimica Acta 381 Feb 2007, p. 63-68

- Quail, M.A. et al. Fecal Calprotectin Complements Routine Laboratory Investigations in Diagnosing Childhood Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis, Vol 15 No 5; May 2009, p. 756-759

- Gaya D.R., et al. Faecal calprotectin in the assessment of Crohn’s disease activity. Q J Med 2005, Vol 98, May 2005, p. 435-441.

- Langhorst, M.D. et al. Noninvasive Markers in the Assessment of Intestinal Inflammation in Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: Performance of Fecal

- Lactoferrin, Calprotectin and PMN-Elastase, CRP, and Clinical Indices. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2008; Vol 103, p. 162-169.

- Berntzen HB, Olmez U, Fagerhol MK, Munthe E. The leukocyte protein L1 in plasma and synovial fluid from patients with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis. Scand J Rheumatol 1991; 20(2): 74-82.

- Bjerke K, Halstensen TS, Jahnsen F, Pulford K, Brandtzaeg P. Distribution of macrophages and granulocytes expressing L1 protein (calprotectin) in human Peyer’s patches compared with normal ileal lamina propria and mesenteric lymph nodes. Gut 1993; 34(10): 1357-63.

- Bjarnason I, Sherwood R. Fecal calprotectin: a significant step in the noninvasive assessment of intestinal inflammation. J Pediatr Gastroent Nutr 2001; 33: 11.

- Brandtzaeg P, Gabrielsen TO, Dale I, Muller F, Steinbakk M, Fagerhol MK. The leucocyte protein L1 (calprotectin): a putative nonspecific defence factor in epithelial surfaces. Adv Exp Med Biol 1995; 371A: 201-6.

- Bunn SK, Bisset WM, Main MJ, Golden BE. Fecal calprotectin as a measure of disease activity in childhood inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2001; 32(2): 171-7

- Campeotto F, Baldassarre M, Butel MJ, Viallon V, Nganzali F, Soulaines P, Kalach N, Lapillonne A, Laforgia N, Moriette G, Dupont C, Kapel N Fecal calprotectin: cutoff values for identifying intestinal distress in preterm infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009 Apr;48(4):507-10.

- Campeotto F, Baldassarre M, Butel MJ, Viallon V, Nganzali F, Soulaines P, Kalach N, Lapillonne A, Laforgia N, Moriette G, Dupont C, Kapel N. Fecal calprotectin: cutoff values for identifying intestinal distress in preterm infants.J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009 Apr;48(4):507-10.

- Campeotto F, Kalach N, Lapillonne A, Butel MJ, Dupont C, Kapel N. Time course of faecal calprotectin in preterm newborns during the first month of life. Acta Paediatr. 2007 Oct;96(10):1531-3. Epub 2007 Aug 20. No abstract available.

- Campeotto F, Butel MJ, Kalach N, Derrieux S, Aubert-Jacquin C, Barbot L, Francoual C, Dupont C, Kapel N. High faecal calprotectin concentrations in newborn infants. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2004 Jul;89(4):F353-5.

- Canani RB, Terrin G, Rapacciuolo L, Miele E, Siani MC, Puzone C, Cosenza L, Staiano A, Troncone R. Faecal calprotectin as reliable non-invasive marker to assess the severity of mucosal inflammation in children with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2008 Jul;40(7):547-53. Epub 2008 Mar 20.

- Canani RB, de Horatio LT, Terrin G, Romano MT, Miele E, Staiano A, Rapacciuolo L, Polito G, Bisesti V, Manguso F, Vallone G, Sodano A, Troncone R. Combined use of noninvasive tests is useful in the initial diagnostic approach to a child with suspected inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2006 Jan;42(1):9-15.

- Carroccio A, Iacono G, Cottone M, Di Prima L, Cartabellotta F, Cavataio F, Scalici C, Montalto G, Di Fede G, Rini G, Notarbartolo A, Averna MR. Diagnostic accuracy of fecal calprotectin assay in distinguishing organic causes of chronic diarrhea from irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective study in adults and children. Clin Chem. 2003 Jun;49(6 Pt 1):861-7.

- Carroccio A, Rocco P, Rabitti PG, Di Prima L, Forte GB, Cefalù AB, Pisello F, Geraci G, Uomo G. Plasma calprotectin levels in patients suffering from acute pancreatitis. Dig Dis Sci. 2006 Oct;51(10):1749-53.

- Costa F, Mumolo MG, Ceccarelli L, Bellini M, Romano MR, Sterpi C, Ricchiuti A, Marchi S, Bottai M. Calprotectin is a stronger predictive marker of relapse in ulcerative colitis than in Crohn’s disease Gut. 2005 Mar;54(3):364-8.

- Costa F, Mumolo MG, Bellini M, Romano MR, Ceccarelli L, Arpe P, Sterpi C, Marchi S, Maltinti G.. Role of faecal calprotectin as non-invasive marker of intestinal inflammation. Dig Liver Dis. 2003 Sep;35(9):642-7.

- D’Incà R, Dal Pont E, Di Leo V, Benazzato L, Martinato M, Lamboglia F, Oliva L, Sturniolo GC Can calprotectin predict relapse risk in inflammatory bowel disease? Am J Gastroenterol. 2008 Aug;103(8):2007-14.

- D’Incà R, Dal Pont E, Di Leo V, Ferronato A, Fries W, Vettorato MG, Martines D, Sturniolo GC. Calprotectin and lactoferrin in the assessment of intestinal inflammation and organic disease. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2007 Apr;22(4):429-37. Epub 2006 Jul 13.

- Dale I, Fagerhol MK, Naesgaard I. Purification and partial characterization of a highly immunogenic human leukocyte protein, the L1 antigen. Europ J Biochem 1983; 134(1): 1-6.

- Fagerhol MK. Calprotectin, a faecal marker of organic gastrointestinal abnormality. Lancet 2000; 356(9244):1783-4.

- Fagerhol MK, Andersson KB, Naess-Andresen CF, Brandtzaeg P, Dale I. Calprotectin (The L1 Leukocyte Protein) In: VL Smith & JR Dedman (Eds): Stimulus Response Coupling. The Role of Intracellular Calcium-Binding Proteins, CRC Press, Boca Raton, Fla., USA, 1990, pp. 187-210.

- Gilbert JA, Ahlquist DA, Mahoney DW, Zinsmeister AR, Rubin J, Ellefson RD. Fecal marker variability in colorectal cancer: calprotectin versus hemoglobin. Scand J Gastroenterol 1996; 31(10):1001-5.

- Johne B, Kronborg O, Ton HI, Kristinsson J, Fuglerud P. A new fecal calprotectin test for colorectal neoplasia. Clinical results and comparison with previous method. Scand J Gastroenterol 2001; 36(3): 291-6.

- Johne B, Fagerhol MK, Lyberg T, Prydz H, Brandtzaeg P, Naess-Andresen CF, Dale I. Functional and clinical aspects of the myelomonocyte protein calprotectin. Molecular Pathology 1997; 50(3):113-23.

- Josefsson S, Bunn SK, Domellöf M. Fecal calprotectin in very low birth weight infants. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2007 Apr;44(4):407-13.

- Kristinsson J, Armbruster CH, Ugstad M, Kriwanek S, Nygaard K, Ton H, Fuglerud P. Fecal excretion of calprotectin in colorectal cancer; relationship to tumor characteristics. Scand J Gastroenterol 2001; 36(2):202-7.

- Kristinsson J, Roseth A, Fagerhol MK, Aadland E, Schjonsby H, Bormer OP, Raknerud N, Nygaard K. Fecal calprotectin concentration in patients with colorectal carcinoma. Disease of the Colon & Rectum1998; 41(3):316-21.

- Kronborg O, Ugstad M, Fuglerud P, Johne B, Hardcastle J, Scholefield JH, Vellacott K, Moshakis V, Reynolds JR. Faecal calprotectin levels in a high risk population for colorectal neoplasia. Gut 2000; 46(6):795-800.

- Kapel N, Campeotto F, Kalach N, Baldassare M, Butel MJ, Dupont C. Faecal calprotectin in term and preterm neonates. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010 Nov;51(5):542-7. Review.

- Kapel N, Roman C, Caldari D, Sieprath F, Canioni D, Khalfoun Y, Goulet O, Ruemmele FM. Fecal tumor necrosis factor-alpha and calprotectin as differential diagnostic markers for severe diarrhea of small infants.J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005 Oct;41(4):396-

- Kapel N, Barbot L, Gobert JG. New fecal markers: recent developments and perspectives. Ann Pharm Fr. 2004 Nov;62(6):371-5. Review. French.

- Kapel N. Faecal inflammatory markers in nutrition and digestive Disease in children. Arch Pediatr. 2004 May;11(5):403-5. Review. French. No abstract available.

- Laforgia N, Baldassarre ME, Pontrelli G, Indrio F, Altomare MA, Di Bitonto G, Mautone A. Calprotectin levels in meconium. Acta Paediatr. 2003 Apr;92(4):463-6.

- Limburg PJ. Ahlquist DA. Sandborn WJ. Mahoney DW. Devens ME. Harrington JJ. Zinsmeister AR. Fecal calprotectin levels predict colorectal inflammation among patients with chronic diarrhea referred for colonoscopy. American Journal of Gastroenterology 2000; 95(10):2831-7.

- Meucci G, D’Incà R, Maieron R, Orzes N, Vecchi M, Visentini D, Minoli G, Dal Pont E, Zilli M, Benedetti E, Virgilio T, Tonutti E. Diagnostic value of faecal calprotectin in unselected outpatients referred for colonoscopy: A multicenter prospective study. Dig Liver Dis. 2010 Mar;42(3):191-5. Epub 2009 Aug 19.

- Montalto M, Gallo A, Ferrulli A, Visca D, Campobasso E, Cardone S, D’Onofrio F, Santoro L, Covino M, Mirijello A, Leggio L, Gasbarrini G, Addolorato G. Fecal calprotectin concentrations in alcoholic patients: a longitudinal study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011 Jan;23(1):76-80.

- Montalto M, Gallo A, Ianiro G, Santoro L, D’Onofrio F, Ricci R, Cammarota G, Covino M, Vastola M, Gasbarrini A, Gasbarrini G. Can chronic gastritis cause an increase in fecal calprotectin concentrations?World J Gastroenterol.2010 Jul 21;16(27):3406-10

- Montalto M, Gallo A, Curigliano V, D’Onofrio F, Santoro L, Covino M, Dalvai S, Gasbarrini A, Gasbarrini G Clinical trial: the effects of a probiotic mixture on non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug enteropathy – a randomized, double-blind, cross-over, placebo-controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2010 Jul;32(2):209-14. Epub 2010 Apr 7.

- Montalto M, Santoro L, Dalvai S, Curigliano V, D’Onofrio F, Scarpellini E, Cammarota G, Panunzi S, Gallo A, Gasbarrini A, Gasbarrini G. Fecal calprotectin concentrations in patients with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth. Dig Dis. 2008;26(2):183-6. Epub 2008 Apr 21.

- Montalto M, Santoro L, Curigliano V, D’Onofrio F, Cammarota G, Panunzi S, Ricci R, Gallo A, Grieco A, Gasbarrini A, Gasbarrini G. Faecal calprotectin concentrations in untreated coeliac patients. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2007 Aug;42(8):957-61.

- Montalto M, Curigliano V, Santoro L, Armuzzi A, Cammarota G, Covino M, Mentella MC, Ancarani F, Manna R, Gasbarrini A, Gasbarrini G. Fecal calprotectin in first-degree relatives of patients with ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007 Jan;102(1):132-6. Epub 2006 Nov 13.

- Olafsdottir E, Aksnes L, Fluge G, Berstad A. Faecal calprotectin in infants with infantile colic, healthy infants, children with inflammatory bowel disease, children with recurrent abdominal pain and healthy children. Acta Paediatr 2002; 91: 45. Roseth AG. Fagerhol MK. Aadland E. Schjonsby H. Assessment of the neutrophil dominating protein calprotectin in feces. A methodologic study. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology 1992; 27(9):793-8. Roseth AG. Aadland E. Jahnsen J. Raknerud N. Assessment of disease activity in ulcerative colitis by faecal calprotectin, a novel granulocyte marker protein. Digestion1997; 58(2):176-80.

- Roseth AG. Schmidt PN. Fagerhol MK. Correlation between faecal excretion of indium-111-labelled granulocytes and calprotectin, a granulocyte marker protein, in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology 1999; 34(1):50-4.

- Roseth AG, Fagerhol MK, Aadland E, Schjonsby H. Assessment of the neutrophil dominating protein calprotectin in feces. A methodologic study. Scand J Gastroenterol 1992; 27(9):793-8.

- Roseth AG, Kristinsson J, Fagerhol MK, Schjonsby H, Aadland E, Nygaard K, Roald B. Faecal calprotectin: a novel test for the diagnosis of colorectal cancer? Scand J Gastroenterol 1993; 28(12):1073-6.

- Roseth AG, Aadland E, Grzyb K. Normalization of faecal calprotectin: a predictor of mucosal healing in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004 Oct;39(10):1017-20.

- Scarpa M, D’Incà R, Basso D, Ruffolo C, Polese L, Bertin E, Luise A, Frego M, Plebani M, Sturniolo GC, D’Amico DF, Angriman I. Fecal lactoferrin and calprotectin after ileocolonic resection for Crohn’s disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007 Jun;50(6):861-9.

- Tibble JA, Bjarnason I. Department of Medicine, Guy’s, King’s, St Thomas’s Medical School, Bessemer Road, London SE5 9PJ, UK.Non-invasive investigation of flammatory bowel disease.

- Tibble JA, Bjarnason I. Department of Medicine, Guy’s, King’s, St. Thomas’s Medical School, London, UK. Fecalcalprotectin as an index of intestinal inflammation.

- Tibble JA. Sigthorsson G. Bridger S. Fagerhol MK. Bjarnason I. Surrogate markers of intestinal inflammation are predictive of relapse in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. [Journal Article] Gastroenterology 2000; 119(1):15-22.

- Tibble JA. Sigthorsson G. Foster R. Scott D. Fagerhol MK. Roseth A. Bjarnason I. High prevalence of NSAID enteropathy as shown by a simple faecal test. Gut 1999; 45(3):362-6.

- Tibble J. Teahon K. Thjodleifsson B. Roseth A. Sigthorsson G. Bridger S. Foster R. Sherwood R. Fagerhol M. Bjarnason I. A simple method for assessing intestinal inflammation in Crohn’s disease. Gut 2000; 47(4):506-13.

- Tibble J, Sigthorsson G, Foster R, Fagerhol MK, Bjarnason I. Faecal calprotectin and faecal occult blood tests in the diagnosis of colorectal carcinoma and adenoma. Gut 2001; 49: 402.

- Tibble JA, Bjarnason I. Markers of intestinal inflammation and predictors of clinical relapse in patients with quiescent IBD. Medscape Gastroenterol 2001; 3 (2).

- Ton H. Brandsnes. Dale S. Holtlund J. Skuibina E. Schjonsby H. Johne B. Improved assay for fecal calprotectin. Clinica Chimica Acta 2000; 292(1-2):41-54.

- Kane, S., Sandborn, W., Rufo, P., Zholudev, A., Boone, J., Lyerly, D., Camilleri, M., and S. Hanauer. 2003. Fecal Lactoferrin is a Sensitive and Specific Marker in Identifying Intestinal Inflammation. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 98:1309-1314.

- Parsi, M., Shen, B., Achkar, J., Remzi, F., Goldblum, J., Boone, J., Lin, D., Connor, J., Fazio, V., and B. Lashner. 2004. Fecal Lactoferrin for the Diagnosis of Symptomatic Patients with Ileal Pouch-anal Anastomosis. Gastroenterology 126:1280-1286.

- Buderus, S., Boone, J., Lyerly, D., and M. Lentze. 2003. Fecal Lactoferrin: New Parameter to Monitor Infliximab Therapy. Dig. Dis. and Sciences. 49:1036-1039.

- Langhorst, J., Elsenbruch, S., Mueller, T., Rueffer, A., Spahn, G., Michalsen, A., and G. Dobos. 2005. A Comparison Among Four Neutrophil-derived Proteins in Feces as an Indicator of Disease Activity in Ulcerative Colitis. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 11(12):1085-1091.

- Kayazawa M, Saitoh O, Kojima K et al. Lactoferrin in whole gut lavage fluid as a marker for disease activity in inflammatory bowel disease: comparison with other neutrophil-derived proteins. Am J Gastroenterol 2002; 97: 360-369

- Tibble J, Teahon K, Thjodleifsson et al. A simple method for assessing intestinal inflammation in Crohn´s disease. Gut 2000; 47: 506-5133. van der Sluys Veer A, Brouwer J, Biemond I et al. Fecal lysozyme in assessment of disease activity in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci 1998; 43: 590-595

- Saitoh O, Sugi K, Matsuse R et al. The forms and the levels of fecal PMN-elastase in patients with colorectal diseases. Am J Gastroenterol 1995; 90: 388-393

- Rachmilewitz D and International Study Group. Coated mesalazine versus sulfasalazine in the treatment of active ulcerative colitis: a randomized trial. Br Med J 1989; 298: 82-86

- WALKER C.W., „Fecal occult blood tests reduce colorectal cancer mortality.“, Am Fam Physician. 2007 Jun 1;75(11):1652-3.

- CHIEN-HUA CHIANG, et al. «A comparative study of three fecal occult blood tests in upper gastointestinal bleeding»; Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci May 2006, Vol 22, No 5: 223-228

- HIROFUMI MIYOSHI, et al. «Accuracy of Detection of Colorectal Neoplasia using an Immunochemical Occult Blood Test in Symptomatic Referred Patients: Comparison of Retrospective and Prospective Studies. Internal Medicine Sept. 2000 Vol. 39, No. 9: 701-706.

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin 2009; 59: 225-249

- Wei YS, Lu JC, Wang L, Lan P, Zhao HJ, Pan ZZ, Huang J, Wang JP. Risk factors for sporadic colorectal cancer in southern Chinese. World J Gastroenterol 2009; 15: 2526-2530

- Lei T, Mao WM, Yang HJ, Chen XZ, Lei TH, Wang X, Ying Q, Chen WQ, Zhang SW. [Study on cancer incidence through the Cancer Registry Program in 11 Cities and Counties, China.]. Zhonghua Liuxingbingxue Zazhi 2009; 30: 1165-1170

- Hewitson P, Glasziou P, Watson E, Towler B, Irwig L. Cochrane systematic review of colorectal cancer screening using the fecal occult blood test (hemoccult): an update. Am J Gastroenterol 2008; 103: 1541-1549

- Logan RF. Review: faecal occult blood test screening reduces risk of colorectal cancer mortality. Evid Based Med 2009; 14: 15

- Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Brooks D, Saslow D, Brawley OW. Cancer screening in the United States, 2010: a review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin 2010; 60: 99-119

- Mandel JS, Church TR, Bond JH, Ederer F, Geisser MS, Mongin SJ, Snover DC, Schuman LM. The effect of fecal occult-blood screening on the incidence of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2000; 343: 1603-1607

- Labianca R, Beretta GD, Kildani B, Milesi L, Merlin F, Mosconi S, Pessi MA, Prochilo T, Quadri A, Gatta G, de Braud F, Wils J. Colon cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2010; 74: 106-133

- Levin B, Brooks D, Smith RA, Stone A. Emerging technologies in screening for colorectal cancer: CT colonography, immunochemical fecal occult blood tests, and stool screening using molecular markers. CA Cancer J Clin 2003; 53: 44-55

- Collins JF, Lieberman DA, Durbin TE, Weiss DG. Accuracy of screening for fecal occult blood on a single stool sample obtained by digital rectal examination: a comparison with recommended sampling practice. Ann Intern Med 2005; 142: 81-85

- Allison JE, Sakoda LC, Levin TR, Tucker JP, Tekawa IS, Cuff T, Pauly MP, Shlager L, Palitz AM, Zhao WK, Schwartz JS, Ransohoff DF, Selby JV. Screening for colorectal neoplasms with new fecal occult blood tests: update on performance characteristics. J Natl Cancer Inst 2007; 99: 1462-1470

- Oort FA, Terhaar Sive Droste JS, Van Der Hulst RW, Van Heukelem HA, Loffeld RJ, Wesdorp IC, Van Wanrooij RL, De Baaij L, Mutsaers ER, van der Reijt S, Coupe VM, Berkhof J, Bouman AA, Meijer GA, Mulder CJ. Colonoscopycontrolled intra-individual comparisons to screen relevant neoplasia: faecal immunochemical test vs. guaiac-based faecal occult blood test. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2010; 31: 432-439

- Parra-Blanco A, Gimeno-García AZ, Quintero E, Nicolás D, Moreno SG, Jiménez A, Hernández-Guerra M, CarrilloPalau M, Eishi Y, López-Bastida J. Diagnostic accuracy of immunochemical versus guaiac faecal occult blood tests for colorectal cancer screening. J Gastroenterol 2010; 45: 703-712

- Young GP, Cole S. New stool screening tests for colorectal cancer. Digestion 2007; 76: 26-33

- Kronborg O, Regula J. Population screening for colorectal cancer: advantages and drawbacks. Dig Dis 2007; 25: 270-273

- Uchida K, Matsuse R, Miyachi N, Okuda S, Tomita S, Miyoshi H, Hirata I, Tsumoto S, Ohshiba S. Immunochemical detection of human blood in feces. Clin Chim Acta 1990; 189: 267-274

- Burton RM, Landreth KS, Barrows GH, Jarrett DD, Songster CL. Appearance, properties, and origin of altered human hemoglobin in feces. Lab Invest 1976; 35: 111-115

- Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Genetic instability in colorectal cancers. Nature 1997; 386: 623-627

- Tagore KS, Lawson MJ, Yucaitis JA, Gage R, Orr T, Shuber AP, Ross ME. Sensitivity and specificity of a stool DNA multitarget assay panel for the detection of advanced colorectal neoplasia. Clin Colorectal Cancer 2003; 3: 47-53

- Woolf SH. A smarter strategy? Reflections on fecal DNA screening for colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 2755-2758

- Hakama M, Coleman MP, Alexe DM, Auvinen A. Cancer screening: evidence and practice in Europe 2008. Eur J Cancer 2008; 44: 1404-1413

- Hoff G, Grotmol T, Thiis-Evensen E, Bretthauer M, Gondal G, Vatn MH. Testing for faecal calprotectin (PhiCal) in the Norwegian Colorectal Cancer Prevention trial on flexible sigmoidoscopy screening: comparison with an immunochemical test for occult blood (FlexSure OBT). Gut 2004; 53: 1329-1333

- McDonald S, Lyall P, Israel L, Coates R, Frizelle F. Why COMMENTS Chen JG et al. Colorectal cancer screeningWJG|www.wjgnet.com 2688 June 7, 2012|Volume 18|Issue 21|barium enemas fail to identify colorectal cancers. ANZ J Surg 2001; 71: 631-633

- Kahi CJ, Imperiale TF, Juliar BE, Rex DK. Effect of screening colonoscopy on colorectal cancer incidence and mortality. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2009; 7: 770-775; quiz 711

- Rabeneck L, Paszat LF, Hilsden RJ, Saskin R, Leddin D, Grunfeld E, Wai E, Goldwasser M, Sutradhar R, Stukel TA. Bleeding and perforation after outpatient colonoscopy and their risk factors in usual clinical practice. Gastroenterology 2008; 135: 1899-1906, 1906.e1

- Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Brawley OW. Cancer screening in the United States, 2008: a review of current American Cancer Society guidelines and cancer screening issues. CA Cancer J Clin 2008; 58: 161-179

- Pox CP, Schmiegel W. Role of CT colonography in colorectal cancer screening: risks and benefits. Gut 2010; 59: 692-700

- Chiang CH, Jeng JE, Wang WM, Jheng BH, Hsu WT, Chen BH. A comparative study of three fecal occult blood tests in upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2006; 22: 223-228

- Sugi K, Saitoh O, Hirata I, Katsu K. Fecal lactoferrin as a marker for disease activity in inflammatory bowel disease: comparison with other neutrophil-derived proteins. Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91: 927-934

- Ward DG, Suggett N, Cheng Y, Wei W, Johnson H, Billingham LJ, Ismail T, Wakelam MJ, Johnson PJ, Martin A. Identification of serum biomarkers for colon cancer by proteomic analysis. Br J Cancer 2006; 94: 1898-1905

- Ahmed N, Oliva KT, Barker G, Hoffmann P, Reeve S, Smith IA, Quinn MA, Rice GE. Proteomic tracking of serum protein isoforms as screening biomarkers of ovarian cancer. Proteomics 2005; 5: 4625-4636

- Saitoh O, Kojima K, Kayazawa M, Sugi K, Tanaka S, Nakagawa K, Teranishi T, Matsuse R, Uchida K, Morikawa H, Hirata I, Katsu K. Comparison of tests for fecal lactoferrin and fecal occult blood for colorectal diseases: a prospective pilot study. Intern Med 2000; 39: 778-782

- Hirata I, Hoshimoto M, Saito O, Kayazawa M, Nishikawa T, Murano M, Toshina K, Wang FY, Matsuse R. Usefulness of fecal lactoferrin and hemoglobin in diagnosis of colorectal diseases. World J Gastroenterol 2007; 13: 1569-1574

- Sheng JQ, Li SR, Wu ZT, Xia CH, Wu X, Chen J, Rao J. Transferrin dipstick as a potential novel test for colon cancer screening: a comparative study with immuno fecal occult blood test. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2009; 18: 2182-2185

- Lönnerdal B, Iyer S. Lactoferrin: molecular structure and biological function. Annu Rev Nutr 1995; 15: 93-110

- Chew MH, Suzanah N, Ho KS, Lim JF, Ooi BS, Tang CL, Eu KW. Colorectal cancer mass screening event utilising quantitative faecal occult blood test. Singapore Med J 2009; 50: 348-353

- Mandel JS, Church TR, Ederer F, Bond JH. Colorectal cancer mortality: effectiveness of biennial screening for fecal occult blood. J Natl Cancer Inst 1999; 91: 434-437

- Allerberger F., et al. 2003. Hemolytic-uremic syndrome associated with enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O26:H infection and consumption of unpasteurized cow’s milk. Int. J. Infect. Dis.7:42-45. [PubMed]

- Bastian S. N., Carle I., Grimont F. 1998. Comparison of 14 PCR systems for the detection and subtyping of stx genes in Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli. Res. Microbiol. 149:457-472.[PubMed]

- Bavaro M. F. 2009. Escherichia coli O157: what every internist and gastroenterologist should know.Curr. Gastroenterol. Rep. 11:301-306. [PubMed]

-

Belanger S. D., Boissinot M., Menard C., Picard F. J., Bergeron M. G. 2002. Rapid detection of Shiga toxin-producing bacteria in feces by multiplex PCR with molecular beacons on the Smart cycler. J. Clin. Microbiol. 40:1436-1440. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

|

|